The European automotive industry, which only recently emerged from a severe crisis in microchip supplies, is once again facing the threat of widespread disruption, this time caused not by the pandemic, but by escalating geopolitical tensions. The source of the potential problem is a serious conflict between the Dutch government and the Chinese owners of Nexperia, a global leader in the production of semiconductor components, essential for modern electronics. Dutch authorities invoked a rare mid-century law allowing them to block decisions of strategic companies, allowing them to remove the Chinese head of a subsidiary and triggering Beijing's immediate response with a ban on chip exports.

The Netherlands' decisive action was prompted by a court case that revealed serious conflicts of interest within Nexperia's management. It was established that the ousted Chinese manager wielded significant influence within the parent corporation, Wingtech, and controlled Chinese factories producing silicon wafers, the basis for microchip manufacturing. The investigation revealed that Nexperia purchased hundreds of millions of dollars worth of these wafers from an affiliate, with order volumes far exceeding the Dutch manufacturer's objective technological needs, paving the way for the uncontrolled transfer of advanced technologies.

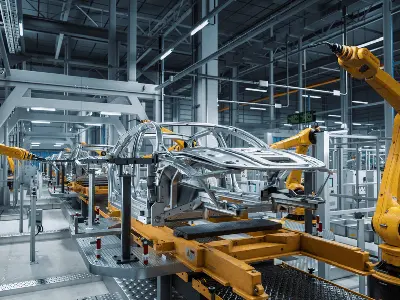

China's response was immediate and took the form of an official ban on the export of chips produced at Nexperia's facilities. This decision has profound implications for global markets, as the company's Chinese production lines annually manufacture over fifty billion microchips used in countless devices, from home appliances to modern automobiles. Major automakers, including German concerns Volkswagen and BMW, have already expressed serious concern, warning of imminent disruptions to assembly lines if the situation isn't resolved in the coming months.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that even Nexperia's European plant, located in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, is not the final link in the production chain, producing only the silicon wafers that are subsequently shipped to China for the complex process of slicing and final packaging into finished components. This production structure has once again demonstrated the vulnerability of the European industry, which has become heavily dependent on Asian, and particularly Chinese, production facilities, where key technological processes were previously relocated in pursuit of cost efficiency.

According to current analyst estimates, European automakers have approximately six months' worth of microchip inventory, leaving a very limited window for complex diplomatic negotiations. Direct dialogue between the Netherlands and China currently appears to be the only reasonable way to avoid a full-blown crisis, as the deployment of new production lines or the replacement of subcontractors in the microelectronics sector requires many months of hard work and colossal financial investments, and there is simply no available production capacity on the global market at the moment that could immediately compensate for such a volume.